By Benita Whitehorn and Sazzad Hossain

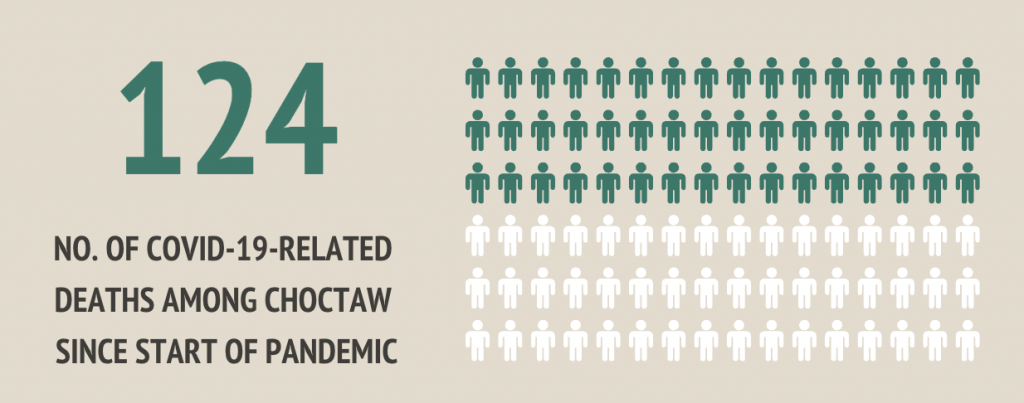

Clarice Billy is a survivor. A petite, soft-spoken Choctaw woman who adores and lives for her four grandsons and great-grandson, she is one of the many members of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians who has experienced the dangerous combination of diabetes and COVID-19. Diabetes is prevalent among the Choctaw, and the tribe has experienced a high number of COVID cases with 124 related deaths since the pandemic began.

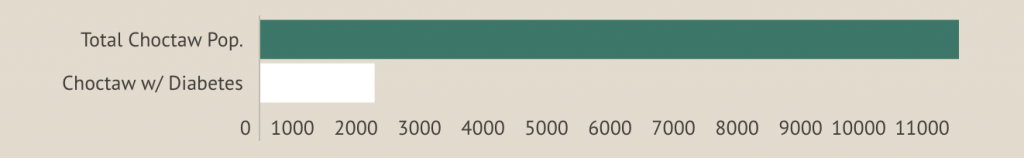

The Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians, comprising around 11,000 members in the east-central part of the state, has known adversity long before diabetes and COVID-19 came along, but it is a tenacious tribe. About 4,000 of their ancestors stayed put when the U.S. took over their land and moved most of the Choctaw to Oklahoma as part of the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek in 1830. And they experienced extreme poverty until 1969, when the tribe began to develop a variety of successful businesses, including the Pearl River Resort, that allowed them to improve their plight.

Billy has lived with diabetes since 1999 and contracted COVID-19 on May 18 of this year. Since then, she has had trouble keeping her blood sugar level down, in addition to experiencing fever and shortness of breath. She has been admitted to three different hospitals, came down with pneumonia, was put on a ventilator, and still has trouble breathing when she does physical activities such as housework.

Clarice Billy gathers with her family at the annual Choctaw Indian Fair.

“My diabetes, it’s gone up haywire,” Billy said. “I don’t know what’s happening. I never had that problem before. I try to keep it the way it usually does, but it doesn’t help. And I’ve been in the hospital for what, almost three months with it (COVID-19).”

While Billy was on a ventilator in the hospital, she could only wave to her family through a window, but their visits gave her a reason to live.

“The youngest one said, ‘Mama, when you get out of the hospital, you’re not going to your house, you’re going to come to my house and stay with me,’” Billy said.

And that’s what she did.

Dr. Chandrashekhar Joshi, a primary care physician who has worked in the diabetes department of the Choctaw Health Center for 32 years, treats Billy there. A renovation in 2015 modernized and doubled the size of the former facility. Along the spacious, gleaming hallways, offices display signs in English as well as Choctaw. Profits from the Choctaw band’s casinos and other businesses helped pay for the center, as well as other services in the community.

Dr. Chandrashekhar Joshi, a primary care physician who has worked in the diabetes department of the Choctaw Health Center for 32 years, said uncontrolled diabetes worsens COVID-19 in patients.

Joshi, a native of India, is passionate about treating his diabetic patients whom he much prefers to see in person, though COVID-19 has made that more difficult until recently. He said the virus has aggravated diabetes in the Choctaw population.

“I think diabetes, per se, is a very challenging disease,” he said. “All those challenges, they are magnified with the pandemic.”

“So (with COVID-19) we also saw the surge in the high sugars, and the uncontrolled diabetes has become even worse,” Joshi said. “At the same time, many of the treatments some of the patients received like steroids and stuff like that, that makes the sugar even worse. So it’s kind of both ways. The infection makes the sugar to go high, and the treatment makes the sugar to go high.”

In June 2020, health officials in Mississippi reported that Native Americans in the state were almost eight times more likely to become infected with coronavirus and were dying at a disproportionately higher rate than anyone else in the state.

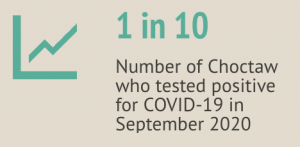

As of September 2020, the pandemic had hit the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians harder than any major city in the nation — and 10 times harder than the rest of Mississippi. About one in 10 had tested positive for COVID-19.

As of September 2020, the pandemic had hit the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians harder than any major city in the nation — and 10 times harder than the rest of Mississippi. About one in 10 had tested positive for COVID-19.

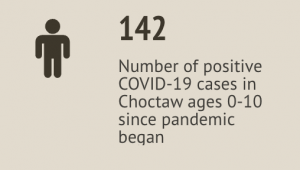

And as of Nov. 15, 2021, the Choctaw tribe recorded 2,475 positive cases of coronavirus and 124 related deaths since the start of the pandemic. As of that date, a total of 509,717 positive COVID cases and 10,215 deaths were reported statewide. Among the communities within the Mississippi Choctaw tribe, 49 deaths occurred in Pearl River alone. The highest number of positive cases (506) occurred in the age group 31-40, and 142 positive cases occurred among ages 0-10, according to the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians’ Facebook page.

During the pandemic, a lot of Choctaw diabetic patients couldn’t go to the grocery because they were in quarantine or their driver had COVID-19; therefore, they would eat whatever was available, Joshi said. They also couldn’t pick up their medication, so Choctaw Health Center staff started delivering medication to patients, he said.

During the pandemic, a lot of Choctaw diabetic patients couldn’t go to the grocery because they were in quarantine or their driver had COVID-19; therefore, they would eat whatever was available, Joshi said. They also couldn’t pick up their medication, so Choctaw Health Center staff started delivering medication to patients, he said.

Stressing over the pandemic factored as another barrier for diabetes patients.

“Some of the stresses in their life, they’re so overwhelming that they don’t pay attention to their own health, but they’re more worried about their grandkid(s) or something like that,” Joshi said. “And those patients, now when they have even more stress in their life, automatically, it becomes more difficult for them to comply with the medication.”

Billy is one of those tribe members who ignored her symptoms.

Choctaw Health Center

“My oldest lives with me, but my youngest one was the one that said, ‘Mama, you’re sick, (you) need to go to the doctor.’ And stubborn as I am, I said, ‘I’m not sick. I’m all right,’” she said. “Then my brother passed away with it, and I went to his funeral. But after that, I just went down. And so he brought me to the hospital and said, ‘Well, Mom, I’m just gonna take you to the hospital. I know you have it.’ So he took me up there. And that’s when they told me I was positive.”

To combat COVID-19, the Choctaw leaders established a COVID-19 hotline, put quarantine rules into effect, and set up drive-thru testing, vaccination sites and a triage tent outside the Choctaw Health Center.

“We were seeing a lot of patients who live in multifamily groups here,” said Dr. Christian Beebe, a contract emergency room physician working for the Choctaw Health Center. “So we were seeing these clusters early on, where several sick patients would show up together.”

A Choctaw Health Center employee waits to check in any visitors and patients at the front desk.

Beebe said at the triage tent, younger or less symptomatic patients could be evaluated and treated outside, while sicker and/or older people with more comorbidities could be brought inside and treated.

He said sometimes he would see patients coming in who had had multiple family members die from COVID, including sometimes younger patients.

“I’m thinking of someone in their young 20s, who actually had both parents already, you know, die of COVID,” he said. “And then they catch the illness. So of course, they’re terrified. And so some of those situations are really heartbreaking.”

Diabetes Prevention before COVID

In 2017, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that American Indians and Alaska Natives have the highest prevalence of diabetes in the United States, more than twice the prevalence of diabetes among non-Hispanic whites. The problem may be at least partly traced to when these indigenous populations’ diet changed to an “American” diet, high in calories and sugar.

Due to a growing epidemic of diabetes in Native Americans, Congress established the Special Diabetes Program for Indians in 1997, and the Choctaw Health Center follows that program. Type 2 diabetes is prevalent among the Choctaw (close to 1,800 diabetics among 11,000 residents, or over 16%), but moderate diet and exercise can delay and possibly prevent the disease.

The tribe tries to promote a healthy lifestyle through education such as the annual Unity Walk, when stickball players representing teams from 28 different communities raise awareness about diabetes.

Joshi takes a holistic approach to treating his patients and makes sure they have access to all the services they might need such as dental, foot and wound care, nutrition advice and behavioral health.

He even designed a program called “Club Seven” to motivate his patients to control their diabetes. Patients get an A1C test every three months. Less than seven is a good result.

A quilt wall hanging in the Choctaw Health Center displays some tribal traditions such as stickball (top left).

“So I called them Club Seven people,” Joshi said. “And then we give them a certificate and take their pictures. … Usually they look at the picture, and it motivates them. … I used to threaten them that if their seven becomes higher two times consecutively, I’ll have to take their picture down.”

Joshi said the pandemic could spur his diabetic patients to take better care of their health, though some of his patients have lost all progress in controlling their disease. He’s not giving up hope, though.

“If you lose the hope, you will not have any purpose to be here. OK, so I am an eternally optimistic person.”

Honoring Those Who Died

While Billy is lucky enough to be recovering from COVID-19, many of the people she knew had died from it, and so she doesn’t feel so lucky.

“How could I survive, but they didn’t survive? That’s what was in my mind when some of the people that I knew passed away.”

To honor the over 100 Choctaw tribe members who died from the disease, the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians dedicated a COVID-19 memorial to them in March 2021.

“You know, thinking about that number, that number may sound small, but to a community that only has a little over 11,000 tribal members, that’s a big impact,” said Fred Willis, public information manager with the Choctaw Public Information Office.

Lake Pushmataha provides a peaceful spot for family and friends to mourn those they lost to COVID-19.

The pandemic may have slowed progress in combating diabetes in the Choctaw community, but the Mississippi Choctaw are used to setbacks, such as when they lost 25% of their population to the 1918 flu pandemic.

“You know, you do have your moments when you get tired of doing things that you have to do in order to survive, but at the same time, that’s kind of part of our genetic makeup,” Willis said. “As Mississippi Choctaw … our ancestors have done everything they could to survive.”

Willis said the Choctaw community still faces challenges in dealing with COVID-19 and other health issues such as diabetes.

“But now it’s like, OK, we need to stand together. … It’s that tenacity that got us to where we are today.”

The Golden Moon Casino, a landmark in Philadelphia, is part of the Choctaws’ Pearl River Resort, which includes another casino, a waterpark and golf course.