Olivia Reeves

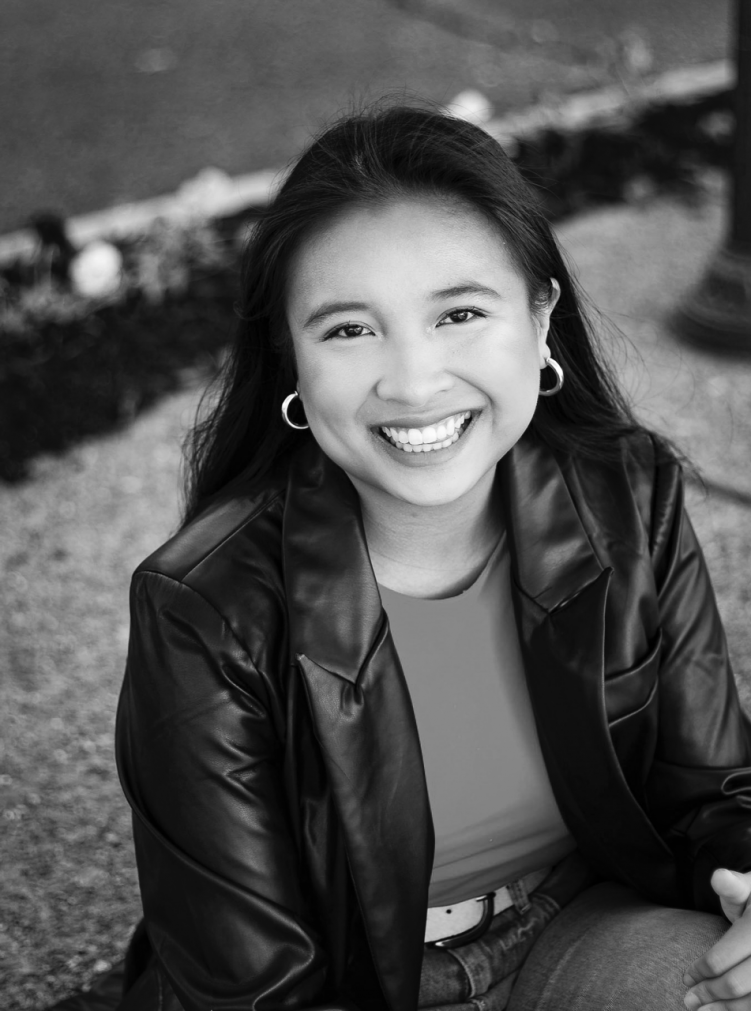

Tiffany Nguyen works at a makeshift manicure table in her Oxford apartment, her bright smile and brown eyes in the glow of an LED lightbulb, nail polish bottles scattered before her on a white table.

Across from her, a client is chatting while getting a pink cow print design on her nails. The work is not new to Nguyen, dressed in a pair of sweatpants, and who for several years before attending Ole Miss worked at Nails 1st, the salon her family owns in Indianola.

Nguyen was less than a year old, her younger siblings, Jennifer and Richard, not even born, when her parents, Vietnamese immigrants, made Indianola home. They had moved from Michigan to the Delta, encouraged by their cousin who was selling a nail salon. The Nguyen family began their own nail business from this shop in Indianola.

The Nguyens’ successful business reflects both their hard work and the challenges encountered on a path to acculturation, reflecting the daily obstacles they faced, some hostile.

Nguyen, 21, a senior biochemistry major at Ole Miss, said that in the face of the hardships her parents endured in owning a business and becoming members of the Indianola community, her generation is a source of hope for society.

Her identity is forged both by Vietnamese culture in her Mississippi community – welcoming, understanding, always wanting to learn more, she said, for the most part.

However, Nguyen has, at times, feared for her parents’ safety, because English is their second language. Her worries do not hinder her from loving and embracing who she is and where she comes from, she said.

She believes people are becoming more willing to acknowledge tradition while rejecting its stereotypes. Empathy is essential to social change within a democracy, she said, and her generation is less afraid to express opinions.

Being from the Delta is a source of pride. “There was never a point where I felt like bullied because of my race,” she said.

On campus, and among her many activities, she is Social Chair of the Ole Miss Vietnamese American Student Association. This organization helps her share passion for her culture with others – from modeling traditional Vietnamese dress for various events, to sharing a Vietnamese word of the day.

Nguyen’s parents came to America from Hue, a city in central Vietnam. As a teen, her father sought opportunity abroad, traveling first alone to Hong Kong and then to the United States in the 1980s, his future spouse to follow.

Her father prevailed in the face of financial hardships, relying on the generosity of family scattered across the country who would offer him lodging, while he learned English.

“Whenever my dad first came over, he didn’t have the money to support himself, like he didn’t have any money at all, and he couldn’t get a job either because he didn’t know what to do,” said Nguyen.

Her father studied electrical engineering but stopped because learning English proved overly difficult. “He excelled through his whole degree, except when he got to English and writing, and so because of that he couldn’t graduate, which was really sad because he excelled in everything else,” she recalled.

Leaving school forced Nguyen’s father to work a series of jobs – janitor, factory worker, electrical engineering assistant. He found a foothold as a nail technician after being introduced to working with nails through relatives.

The business provided the Nguyens a livelihood. Her parents would work from 7 a.m. to 9 p.m., Monday through Saturday. “We were always inside of the nail salon with them. When my brother was a baby, my mom even had a crib in the nail salon,” recalled Nguyen.

Growing up doing nails in her family’s shop made her realize that using her hands was a talent. She hopes to study abroad after graduation before applying to dental school. She plans to settle in the Delta.

As Vietnamese business owners, the Nguyens have gained loyal customers over the years. Not all showed respect to her family, though, she said.

“They go in there and make fun of mom and dad to their faces, and that’s something that they deal with every single day. There’s never a day that they don’t deal with that. Sometimes it gets to the point where there will be table shoving and physical damage,” she explained, adding that more public attention should be brought to these aggressions.

“It stinks, because I want to publicize stuff like this, but Mom and Dad are afraid that if we publicize it, then people will just try to do that more,” she said. “I just wish that business owners, especially Asian business owners, weren’t disrespected so much, because I feel like that’s something really big that not many people talk about,” she said.

Her family has encountered a mostly supportive community, but Nguyen still worries about the safety of her parents in situations where not everyone is as welcoming or warm.

“Whenever my parents go into stores, I’m always afraid because they don’t speak a lot of English, so they can’t really stand up for themselves. It’s really hard for me, my brother, and sister to see stuff like that, just because you never want to see your parents being treated awfully,” she said.

While the nail shop dominated the week, they kept Sundays for family time. “We always worked from Monday till Saturday, and Sunday was like our family day. Mom and Dad always made sure that we would spend it together and would make sure it was for us,” she recalled.

“Because we’re from the Delta, everything we needed involved driving at least two or three hours away. So, we would wake up Sunday morning and either go to Jackson or Memphis.” They would often stop at an Asian market for her mom to buy food for the week.

Her parents ensured that Sunday errands could be fun, too. Nguyen and her siblings would play at Chuck E. Cheese, visit a pet store, or go shopping. If they decided to stay home, the Nguyens spent time together gardening vegetables, mowing the grass, and doing housework.

Growing up with a prioritization on family time influenced Nguyen’s values and beliefs. “Both Mom and Dad always told us it is very important to help give back to people, regardless of how much money you have,” she said.

In 2016, during her junior year of high school, Nguyen’s father and younger siblings got into a bad car accident, and her father had to be airlifted to the hospital in Jackson.

It was a scary day because her father faced the possibility of being paralyzed. The car, an early purchase, was sentimental to her mother because it symbolized her father’s financial stability, so they could get married.

Some residents living near the accident site were friends with the person who had hit her father and were quick to defend that driver. Luckily, a family friend of the Nguyens had also been at the same intersection when the accident occurred and gave the police a more accurate description of what happened, explaining that the wreck was not her father’s fault.

This meant much to her family, as her siblings, who escaped serious injury, were too shocked to process what had taken place. Nguyen said she is thankful many people were willing to be generous during a vulnerable time.

Growing up, Nguyen and her siblings also made a point to pay for everything themselves. “I never asked my dad to pay for anything because my parents sacrificed so much, even just to put me in the school we were enrolled in,” she said.

The community noticed this and decided to help pay for Nguyen’s senior trip. “Everyone in the Delta supported me and supported my family, and they still continue to do that to this day,” said Nguyen.

Just as the family has given back, they have been on the receiving end of Indianola’s generous community spirit.

Such small acts of kindness mattered to Nguyen, as they mirror the same values instilled by her parents. Living in the Delta has allowed Nguyen to further embrace her racial identity. Her friends not only accepted her for her racial identity, but encouraged her to share it.

“They always were willing to listen to me talk about it. They always wanted to eat the food that we had. They always wanted me to go to the store and buy them stuff. They even helped me raise funds for the Vietnamese floods last year,” she said, proudly.

Nguyen hopes her story will create more visibility for Asian Americans and inspire others, especially her younger relatives, to seek more opportunities.

“Every time I do anything, I also want to make sure that other Asian Americans, like the little girls following me, can say, ‘Wow, she did that, and I want to be able to do that too,’” she said.

Olivia Reeves, born in Nam Dinh, Vietnam and raised in Sulphur, Louisiana, is a sophomore at the University of Mississippi majoring in Integrated Marketing Communications. She currently works as a Digital Marketing Intern for Ole Miss Athletics and is passionate about local Oxford restaurants, Ole Miss Baseball, and the Beatles.